Your Ideas Aren’t Finished: How to Retitle, Recover & Repurpose Like a Whole Artist.

How to turn your existing work into new revenue, new readers, and new relevance.

Most creators think their intellectual property lives one life: the book, the painting, the workshop, the song. They imagine IP as a single-use item, like a paper cup—once emptied, it’s done.

But in the Whole Artist universe, IP is more like Tupperware: it stacks, it stores, it travels, and you will absolutely discover forgotten brilliance in the back of the fridge.

Many creators don’t have a “content problem”—they have a visibility and packaging problem. And the real opportunity isn’t creating more. It’s repurposing what you already made but never fully exploited.

Enter the three phases: Retitled, Recovered, Repurposed.

1. Retitled: When your work deserves a better outfit

Sometimes a piece of writing, a talk, or a course doesn’t land—not because the content is wrong, but because it’s wearing the wrong name tag at the conference.

A title is not a label. It’s a signal, a promise, a hook thrown across the room.

Retitling can:

Unlock new genres

Invite new audiences

Modernize evergreen ideas

Rescue a brilliant project from obscurity

Examples:

A memoir chapter becomes a newsletter called The Truth Window.

A discarded essay becomes The Reinvention of Betty.

A technical talk morphs into Wisdom University: Homework for Your Higher Self.

The content didn’t change. The frame did.

And framing is often 80% of the magic.

Rule of thumb:

If a piece is great but ignored, try a new title before trying a rewrite.

2. Recovered: The treasure hunt for forgotten IP

Every creator has a drawer—literal or digital—bursting with unmined assets:

Notes for abandoned books

Workshop outlines

Unsent newsletters

Photographs, drawings, voice memos

Ideas scribbled on café napkins

That 27-page Google Doc, cryptically titled “FINAL-final-use-this-one-FINAL3”

Recovery is the art of recognizing that your past self left you an inheritance.

At The Write Kit, we call this an IP Excavation—and it always yields gold.

Once you gather the fragments, patterns emerge:

“Oh, this is actually a course.”

“This is a card deck.”

“This is a Substack series.”

“This is a talk my future self can give for $2,500.”

“This is a book proposal waiting politely for me to notice.”

You don’t need to create more ideas.

You need to recover the ideas you already created but forgot to monetize.

3. Repurposed: Where the money is

Once your IP is retitled and recovered, repurposing becomes the fun part.

Creators often assume repurposing is about copying and pasting.

But true repurposing is adaptation, not duplication.

A single idea might become:

A Substack series

A short course or masterclass

A keynote or corporate workshop

A paid download

A card deck (your specialty!)

A community challenge

A podcast episode

A branded template

A chapter in a future book

Social media “micro-stories”

Licensing for educational use

This is how intellectual property becomes intellectual prosperity.

Repurposing doesn’t cheapen your work—it multiplies its reach.

The Whole Artist Mindset: Your IP is an ecosystem

When you repurpose IP, you’re not just squeezing more juice from old fruit.

You’re creating:

Sustainability—you earn while working on the next thing.

Longevity—your ideas evolve instead of expiring.

Confidence—you see your body of work with fresh eyes.

Relief—you don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time.

Revenue diversity—one idea, many income streams.

Creativity isn’t linear. Neither is business.

The Whole Artist thrives in cycles, returns, rediscoveries.

A Closing Thought: IP is a living thing

Your intellectual property isn’t static.

It grows as you grow.

It shapes itself to the container you give it.

Sometimes you simply step back, tilt your head, and say:

“Oh. This wasn’t done.

It was just waiting for its second life.”

Retitle it.

Recover it.

Repurpose it.

And watch your creative world expand.

THE RIBS OF THE MATTER

An Essay by Liz Dubelman

Most families have a story they pull out at holidays—the one about Grandma’s secret recipe or Uncle Harold’s regrettable tattoo. My family’s story is about the time two convicts donated their ribs to save my brother’s life.

It was 1957, and medical ethics was still somewhere between “Do what you can” and “Let’s see what happens.” My father—equal parts brilliant, desperate, and absolutely unhinged in the way only a grieving parent can be—managed to convince a Philadelphia hospital and Sing Sing prison to attempt a procedure that had literally never been done before. A sort of bone-marrow-by-proxy: take ribs from two incarcerated men, extract the marrow, and plant it into the fragile body of a two-year-old boy named David.

My brother.

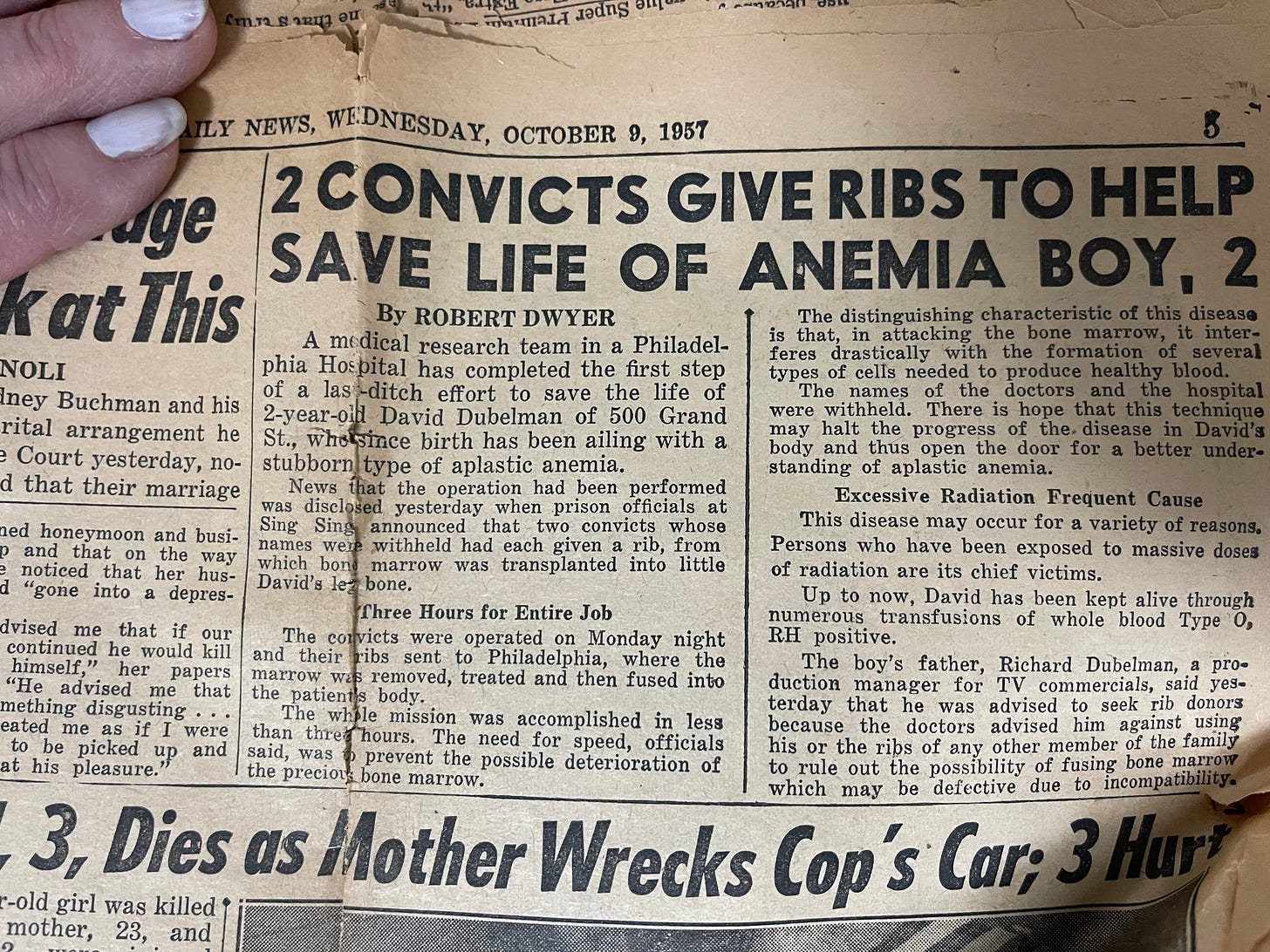

The newspaper clipping reads like a mix of heroism, sci-fi, and bureaucratic courage. “2 CONVICTS GIVE RIBS TO HELP SAVE LIFE OF ANEMIA BOY, 2,” the headline screams in bold, mid-century optimism—back when newspapers still believed in miracles, and punctuation was used sparingly and with purpose.

The men were whisked from Sing Sing to Philadelphia under conditions so secretive you’d think they were being moved to protect national security. Maybe, in my father’s mind, they were. David was his entire nation.

They removed the ribs, extracted the marrow, and transplanted it into my brother. A medical Hail Mary. A swing so wild and hopeful you can feel the desperation radiating off the page seventy years later.

And here’s where the story tilts.

Everyone celebrates the bravery, the innovation, the generosity of the prisoners. But underneath the awe hums the quieter, thornier question:

Can a convict truly give informed consent?

Or is a “yes” behind bars always shaped—if not carved—by the walls around it?

Pivot 1: The Consent Question

This is where ethicists like to mumble and shift in their seats.

Prison is not a place famous for offering choices. It’s a place where you can be punished for saying no, or rewarded for saying yes, even when you don’t fully understand what you’re agreeing to. A place where the very concept of autonomy has been temporarily suspended, like a driver’s license or disbelief during a Marvel movie.

So when two convicts volunteer to have ribs sawed out of their bodies for a child they’ve never met, what exactly is happening?

Heroism?

Manipulation?

Grace?

Coercion?

All of the above?

The truth is, people rarely fit neatly into one category. A prisoner can be guilty and generous. Powerless and profound. Locked up and still capable of opening the world for someone else.

But the question of consent—real, informed, voluntary consent—lingers in the background like a third doctor in the operating room. Silent. Watching. Making notes no one wants to look at.

Even my father’s bravery—his ferocious, unstoppable, nuclear-level love—can’t scrub that complexity away.

Pivot 2: My Brother, the Ghost Larger Than Life

David didn’t survive.

Six months after the transplant, his small body couldn’t hold the miracle together. He died five years before I was born, which means I grew up with the ghost of a brother I never met but who, somehow, outshone me effortlessly. A prodigy of potential.

In my family lore, he was The Child Who Might Have Been Everything. And me? I was the child who had the decency to arrive late, when everyone had settled into their grief like a long, uncomfortable car ride. My very existence was a soft reboot of the Dubelman franchise—a sequel not expected to surpass the original.

Humor is my coping mechanism. It’s cheaper than therapy and requires no insurance authorization. So I’ve always joked that David was clearly going to be much better than me. Better behaved. Better looking. A natural violinist, probably. The kind of child who didn’t leave sandwiches in his backpack long enough to start a new species.

But beneath the humor lives a tender truth:

I was raised in the gravitational pull of a loss that wasn’t mine but defined me anyway.

David’s story became the emotional wallpaper of my childhood. The miracle attempt. The heroic convicts. The doctors trying something radical because hope sometimes demands recklessness. And my father—never the same again, carrying both pride and devastation like twin briefcases he refused to put down.

Pivot 3: My Father, Who Would Have Moved Mountains and Sing Sing Itself

I often wonder how he convinced them.

The doctors.

The prison officials.

The inmates.

Imagine the pitch:

“Hello, I’d like to borrow two ribs from your prisoners and ship them to Philadelphia for experimental transplantation into my toddler. No, this has never been done before. Yes, I promise it will be quick-ish.”

But parents in crisis develop a kind of supernatural charisma. When you look at people through the lens of your child’s survival, they blur into two categories: those who can help, and those who need to get out of the way.

My father’s love was so vast it crossed legal, medical, and ethical boundaries without slowing down to ask for directions. He lived for the possibility that David might live. And when that possibility died, a part of him did too.

Some fathers build treehouses.

Mine built an unprecedented medical procedure.

Pivot 4: The Prisoners—The Men Who Said Yes

I think often about the two men who donated ribs to save a child they didn’t know. Not their child. Not even the child of a fellow prisoner. A stranger’s child.

Maybe they volunteered to feel human again.

Maybe to feel useful.

Maybe they wanted redemption.

Or maybe they were just bored, and the idea of a road trip to a real hospital sounded better than another day in the yard.

I will never know their reasons.

No one does.

But here’s what I do know:

Generosity can bloom in the unlikeliest soils.

Even in a prison yard.

Even in regret.

Even inside a man who has done unforgivable things.

The ethical question remains—but so does the human one:

Why did they say yes?

And would I have said yes, in their position?

The older I get, the less certain I am about my own answer.

Pivot 5: What We Owe to the People Who Tried

David’s death does not negate their gift.

Nor the doctors’ wild hope.

Nor my father’s unstoppable faith.

This story isn’t about the success of a procedure.

It’s about the audacity of trying.

We are so often taught to measure worth in outcomes.

But some things defy metrics.

What is the value of six more months of life?

What is the value of hope, even borrowed hope?

What is the value of a stranger’s rib placed gently into a dying child’s chest?

There are no standard units for that.

Not milliliters, not centimeters, not moral absolutes.

Pivot 6: The Legacy I Carry

I didn’t know my brother.

But I inherited the story of his almost-miracle.

It made me the kind of person who believes in wild attempts.

In trying, even when logic has left the building.

In human beings acting out of impossible generosity.

In the flawed beauty of saying yes, even when the world around you says you shouldn’t have that power.

My father’s grief shaped me, but so did his courage.

And the prisoners’ gift shaped me too—not genetically, but spiritually.

Two men who society wrote off still managed to write themselves into my family story, into my understanding of what people are capable of.

I sometimes think their ribs helped hold me up, in a way.

They gave to one child, and in the end, that gift flowed down to another.

Closing: Consent, Love, and the Impossible

So can a convict give informed consent?

Legally, it’s complicated.

Ethically, it’s thorny.

Personally, it’s the question my family has lived inside for decades.

But here’s what I’ve come to believe:

Consent is a legal structure.

Love is a human impulse.

And hope—messy, unscientific, unreasonable hope—is its own kind of holy madness.

This is a story about consent, yes.

But it is also a story about people doing impossible things for reasons we will never fully understand.

About a father who would have moved mountains, or prisons, or the entire medical establishment, to save his son.

About two men in cages who opened a door in themselves anyway.

About a child who lived long enough to inspire a miracle.

And about the child who came after—me—trying to make sense of it all with a heart full of humor, wonder, and borrowed ribs.

This is fantastic. I'm curious about the deck idea- I know tarot exploded with so many beautiful, fun decks and have long treasured my Eno Oblique Strategies...gonna look into the whole card deck thing. Thanks for these wonderful suggestions Liz.

Liz,

I love your newsletters. They are brilliant.